The Norwegian Green party, the sperregrense and I

When I arrived in Oslo for my Erasmus internship in June 2015, I knew absolutely no one, it was my first time in a foreign country for an extended period of time and I could barely put together a sentence in English. I also happened to arrive on the week of the Oslo Pride.

So on a sunny Saturday morning I walked down to the assembly point in Grønlandsleiret to join the parade, only realising once I got there that things looked a bit different than I expected. Most people getting ready to take part in the tog were members of organised groups, companies and political parties, with everyone else watching on at the sides of the streets.

Not happy to give up, I looked around me and spotted a small but lively group of young people lining up on the street with a bunch of musical instrument. I knew already enough about Norwegian politics at the time to see that they were the local delegation of the Green Party. They seemed friendly enough to ask whether I could join them in the march, and they said yes. I have very good memories of that afternoon.

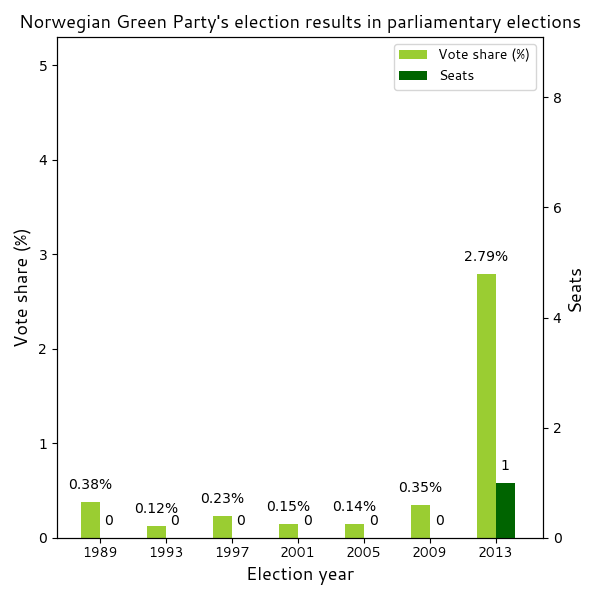

Incidentally, 2015 was a (local) election year in Norway, with elections in all municipalities and counties scheduled for September 14th. Two years earlier, the votes for the Norwegian Green Party had increased eightfold in the previous legislative elections and they had elected their very first MP to the national parliament since the party was founded in 1989. There was a lot of excitement around and the expectation was of further progress in many urban areas of the country, Oslo included. Their flagship proposal in that campaign was to get rid of as many cars as possible from the city centre and expand the bike infrastructure.

My Erasmus started the week after the Pride and it consisted of an internship in a (research) workplace rather than a student exchange at the university, so the chances of socialising with people of my age (in a country where socialising isn’t easy in the first place, especially when you have just arrived) weren’t great. On the other hand, the Green Party volunteers I met at the Pride were young and fun, held a weekly social gathering at the Café Tekehtopa in Sankt Olav Plass 2, and could certainly do with some help with the upcoming electoral campaign in Oslo. The combination of lots of free time to spare and fear of loneliness made me a very opportunistic volunteer for the rest of the summer.

The language barrier meant that I could only help with simple and practical tasks. And to be honest, aside my generic simpathy for the cause, I wasn't even motivated politically all that much. But I learned to make filter coffee, which I was bringing to the those canvassing on the streets. Eventually, I was rewarded with a red T-shirt with the logo and the word GRØNN.

On the evening of the election day, exactly 10 years ago, I was invited to the valgvake, the event in which members, candidates and supporters of a party (as well as journalists and TV commentators) follow the election night. And although I have no memory of it, I have dug up an old email saying that on that night - between 11 and 11.45pm - I was on shift at the door, to be sure no one was bringing alcohol inside the venue. It must have been hard given the overall mood.

Indeed, that night the Oslo Green Party made huge progress and obtained over 10% of the votes, becoming the third largest party in the city. It would have ended up governing the capital in a coalition with other progressive parties until 2023.

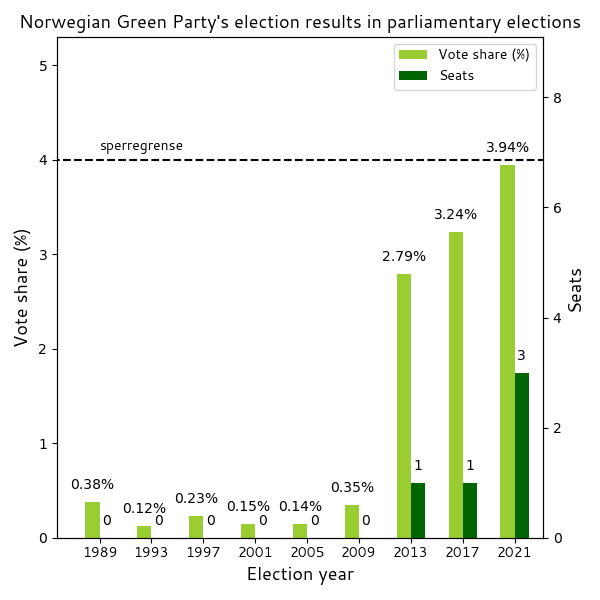

But even more importantly, the Greens won 4.2% of the national share of the votes, and that was the real news. In Norwegian politics, 4% represents the electoral threshold (sperregrense) that guarantees representation in the national parliament1. Replicating that result two years later at the parliamentary elections2 would have meant to gain another 6 or 7 representatives and be officially admitted to the group of (then) seven major political parties shaping national politics.

But as it turned out, things didn't proceed as fast. The Greens failed to clear the sperregrense in 2017, when they obtained 3.2% of the votes, and were left again with a single representative in the Stortinget. And they failed again in 2021, although they got closer than ever (3.94%) and elected two additional MPs.

My Erasmus internship and my time as Green volunteer had ended shortly after the night of the valgvake, when I headed back to Italy. Since then, I moved to Norway to study or work twice more, but somehow I had found other, less opportunistic ways to socialise than volunteering for a political party. I kept, however, following Norwegian politics as a spectator, waiting for the Norwegian Green Party to finally achieve what on that night of September back in 2015 seemed all but a done job.

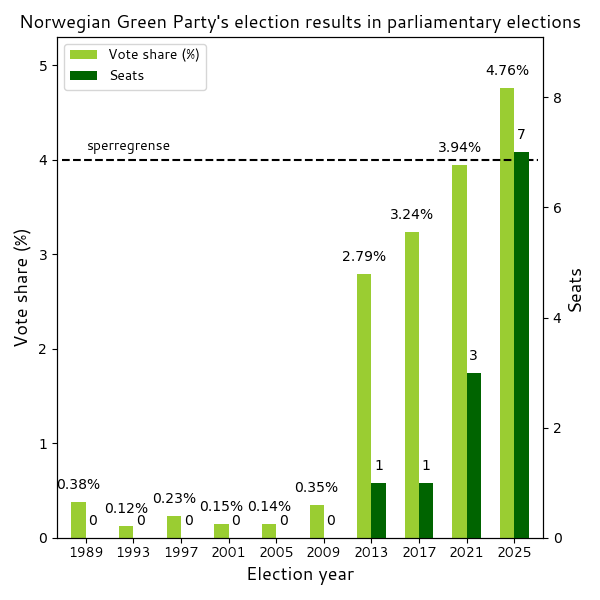

Norway held its most recent parliamentary elections last monday3. The opinion polls looked terrible for the Green Party at the beginning of the summer, then things started to turn. In the weeks and days running up to the elections, their main campaign slogan became ‘Det er mulig’ (it’s possible), in attempt to motivate supporters and voters. The polling average on election day was a whopping 6.2%.

The final result isn’t quite impressive, but at least, 10 years later, the sperregrense spell is finally broken.

Note that this is a sufficient but not a necessary condition. Indeed, the Green Party had elected 1 MP in 2013 obtaining just 2.8% of the votes, thanks to its much stronger result in the electoral district of Oslo (5.6%).

One fascinating aspect of Norwegian politics is how it’s perfectly punctuated by legislative and local elections alternating each other every 2 years on all odd years, normally on the second Monday of September.

And indeed, it was the second Monday of September of an odd year.