The Sea (2002) and the Icelandic fishing industry

A few weeks ago I watched The Sea, an Icelandic movie directed by Baltasar Kormákur. The film came out in 2002 and has meh reviews on both IMDb (6.8) and Rotten Tomatoes (49%). It was nominated to the (first edition of the) Nordic Council Film Prize but didn't win.

The film revolves around the Icelandic fishing industry and the market of fishing quotas. The protagonist (Thordur) is the owner of a small company which catches and processes fish. His firm is struggling to remain economically viable in an industry landscape that is changing rapidly. His stubborness and reluctance to innovate (and eventually to sell the business to a bigger company) is at the centre of the main storyline, and ends up igniting all sort of conflicts and issues.

I personally liked this movie, and I was a bit surprised by the mediocre critical reception. But while I was skimming through some of the reviews, I quickly realised I wasn't adopting the same meter. What I enjoyed the most wasn't the plot, the characters, or the acting (although I think all of them were pretty good). It was, actually, its social and economic background: a snapshot of Iceland in 2002.

I am sure I will visit Iceland at some point, but I haven’t so far. And my current knowledge of it it’s scarce: it's not a place that ends up in the news very often. When it happened recently it was because of yet another volcanic eruption, and because the government announced it would organise a referendum on resuming the accession talks to join the European Union by 2027.

And so while I was watching this movie, I realised there was maybe something interesting to learn about the role of the fishing industry in Iceland, the fishing quotas and the reliance of this sector on foreign workers already in 2002.

The fishing industry

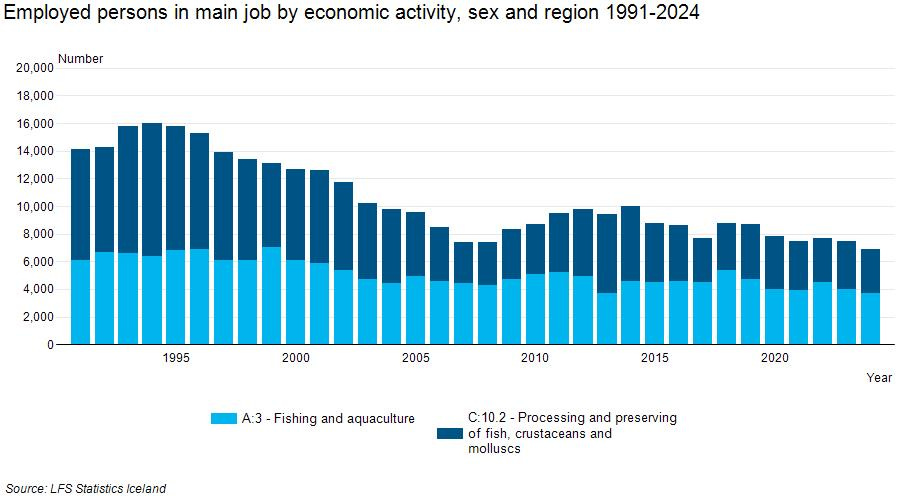

According to Statistics Iceland, around 3 700 people were employed in the ‘fishing and aquaculture’ sector in Iceland in 2024, that is, 1.7% of the total workforce1. To that, one should add those employed in the fish processing industry (3 200 people), taking the total to around 7 000, that is, around 3% of the working population2. Overall, the industry has shrinked by more than half since the mid nineties, when the whole sector employed around 16 000 people, and it had already become significantly smaller by the time the movie was shot and released in 2002, when it employed 11 700 people, or 7.5% of the the working population3.

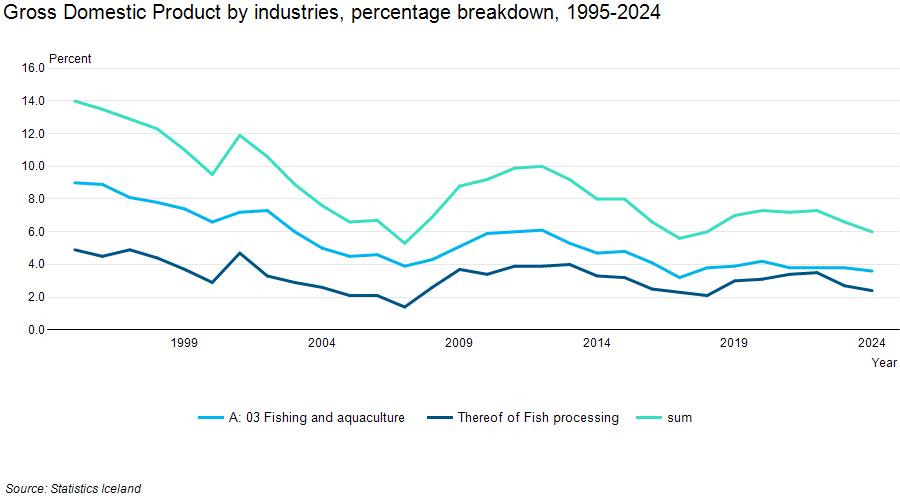

Not surprisingly, the fishing industry has also receded in terms of share of the GDP: here it went form making up almost a seventh of the whole economy (14%) in the early 1990s, to around 10% in 2002 and 6% in 2024.

Fishing quotas

A system of fishing quota has been established in Iceland back in the 1980s to counteract overfishing. What it means is that the companies owning fishing vessels are only allowed to catch a certain amount of fish per year (sometimes divided by species, area, etc), established by the government. Possibly as a consquence of this, Icelandic fishing vessels have been catching less fish lately than they used to. The total catch in 2023 stood at around 1.3 million tonnes, down from a peak of 2.1 million in 2002 (there is a timeseries here).

In addition, since 1990 fishing quotas have been made transferrable, meaning they can be bought and sold4. Over time, the quotas’ system has created an increasingly concentrated industry, where fewer operators and companies own an increasingly larger share of the quotas, as even the official Icelandic government’s website reports:

The quota system has led to more concentrated vessel ownership and fishing quotas. Around 75% of the quotas now belong to 25 of the largest vessel operators and fishing companies in Iceland.

Source: government.is

It’s therefore not surprising that one of the most destabilising event in the movie is the attempt made by a bigger company to buy up Thordur’s smaller business.

Immigration

Another topic recurring many times in the film is immigration. The film seems to suggest that in 2002 the fishing industry in Iceland was strongly dependent on migrant workers to function properly. There is even a scene where the owner of a pub refers to this fact by saying that foreign citizens are taking up jobs that locals don’t want to do anymore. I also noticed that people of asian origin were by far the most represented immigrant group depicted in the film.

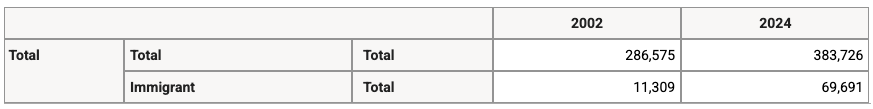

So let’s look at the big picture first. Migration is not a recent phenomenon in Iceland: looking at the net migration figures, the number of foreign citizens has been steadily increasing since the mid-1990s5, decreasing momentarily only in 2009 and 2010 - presumably as a consequence of the financial crash of 2008. Since then, there have been three peaks of new arrivals: one in 2006, one in 2017 and one in 2022. In 2024 more than 69 thousands foreign citizens were living in Iceland, making up 18.1% of the total population. When the movie came out in 2002 the percentage of foreign nationals was around 4%.

As for their country of origin, the composition has also changed slightly over the years. According to some data compiled by OECD available up to 2022, almost 80% of immigrants come from Europe or other nordic countries6 and around 10% from Asia. This proportion was a bit different in 2002, when the share of immigrants from Asia was almost 20% of the total, and a larger proportion was also coming from the other Nordic countries7.

As for the reliance of the fishing industry on the labour of foreing citizens, one can compare the share of foreign citizens employed overall with the proportion of those working specifically in this sector. It turns out, migrants were already overrepresented in this sector in 2002, and they continue to be so today. In 2002, there were a total of 156 070 people in employment (of which 6 360 were foreign citizens), and 11 700 of them worked in the fishing industry (of which 1 450 were foreign nationals)8. This means that while the share of foreign nationals in the workforce as a whole was 4%, they represented more than 12% (i.e. three times as much!) of the people working in the fishing industry. This overrepresentation is smaller today but hasn’t gone away, despite the fishing industry having shrunk in size and the overall foreign workforce having grown to be 24% of the total. In fact, around 38% of all workers employed in the fishing industry in 2023 were foreign citizens (in the manufacturing sector the proportion is almost at 50%)9. So if anything, the reliance of this sector on the work of foreign citizens is more significant today (at leasy in relative term) than it was when the movie was released 23 years ago.

One final interesting aspect of Iceland’s job market is the fact that it has one of the largest share of over-qualified foreign nationals in employment among EU and EEA countries. Data compiled by Eurostat show that more than half of both EU and non-EU citizens working in Iceland are overqualified for their job. In the case of EU citizens, this represents a larger over-qualification rate than that of any EU country.

Same denominator as in footnote 1.

This Statistics Iceland’s Statistical Series report named Wages, income and labour market indicates a total workforce of 156 070 in 2002.

While researching about fishing quotas, I have bumped into this paper by two researchers at the University of Reykjavik, who looked at how this free-market approach had big consequences on Iceland’s fishing villages.

Note that the numbers are initially so slow that this doesn’t even seem to be a direct consequence of entering the EEA, of which Iceland is a member since 1994.

Other than Iceland, that usually refers to Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark.

OECD report, figure 2.3.

OECD report, figure 4.8.